Yikes, evidence-based decisions are taking on water. Decision makers still resist handing the car keys to others, even when machines make better predictions. And government agencies continue to, ahem, struggle with making evidence-based policy. — Tracy Altman, editor

1. Evidence-based home visit program loses funding.

The evidence base has developed over 30+ years. Advocates for home visit programs – where professionals visit at-risk families – cite immediate and long-term benefits for parents and for children. Things like positive health-related behavior, fewer arrests, community ties, lower substance abuse [Long-term Effects of Nurse Home Visitation on Children’s Criminal and Antisocial Behavior: 15-Year Follow-up of a Randomized Controlled Trial (JAMA, 1998)]. Or Nobel Laureate-led findings that “Every dollar spent on high-quality, birth-to-five programs for disadvantaged children delivers a 13% per annum return on investment” [Research Summary: The Lifecycle Benefits of an Influential Early Childhood Program (2016)].

The Nurse-Family Partnership (@NFP_nursefamily), a well-known provider of home visit programs, is getting the word out in the New York Times and on NPR.

Yet this bipartisan, evidence-based policy is now defunded. @Jyebreck explains that advocates are “staring down a Sept. 30 deadline…. The Maternal, Infant and Early Childhood Home Visiting program, or MIECHV, supports paying for trained counselors or medical professionals” where they establish long-term relationships.

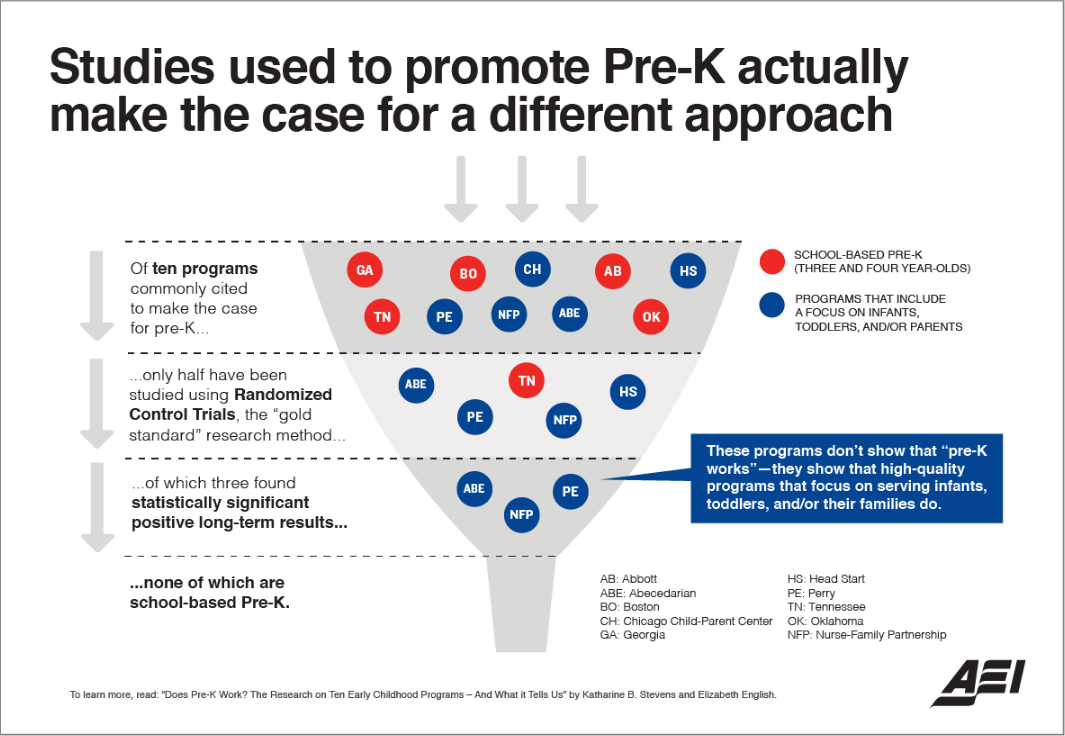

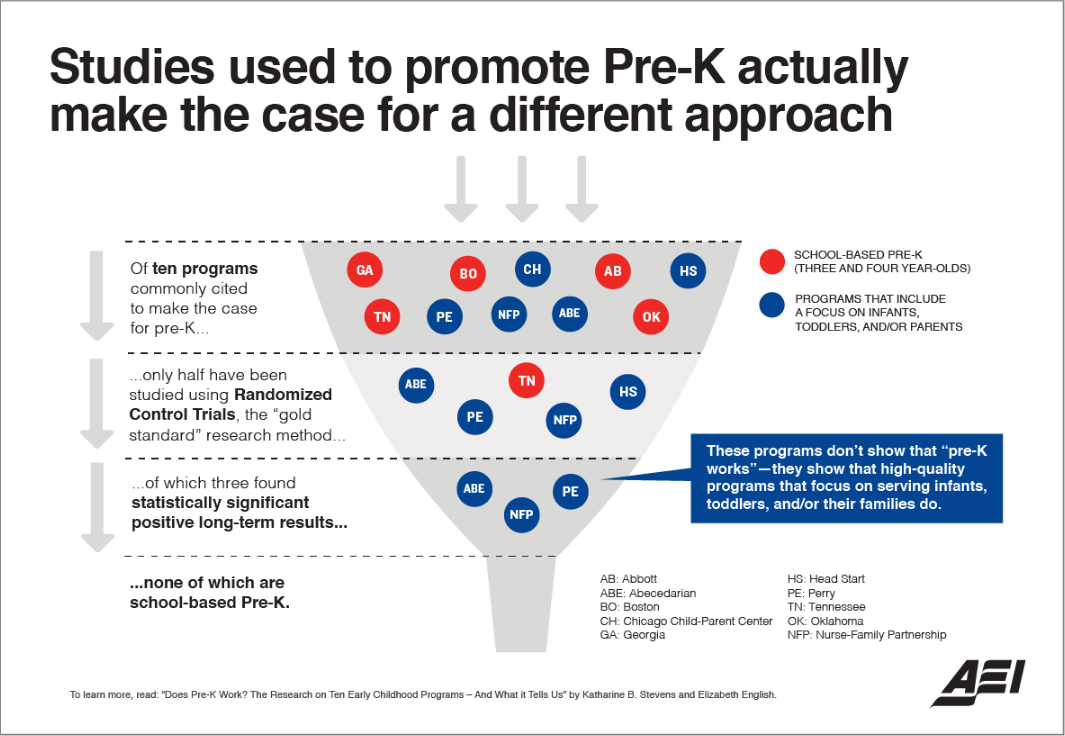

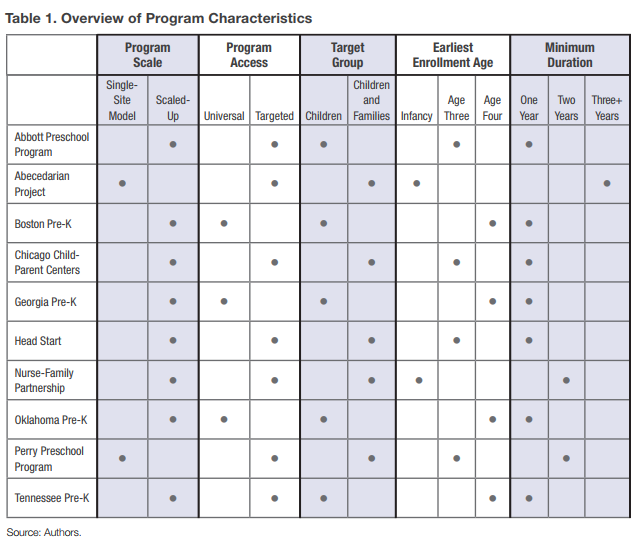

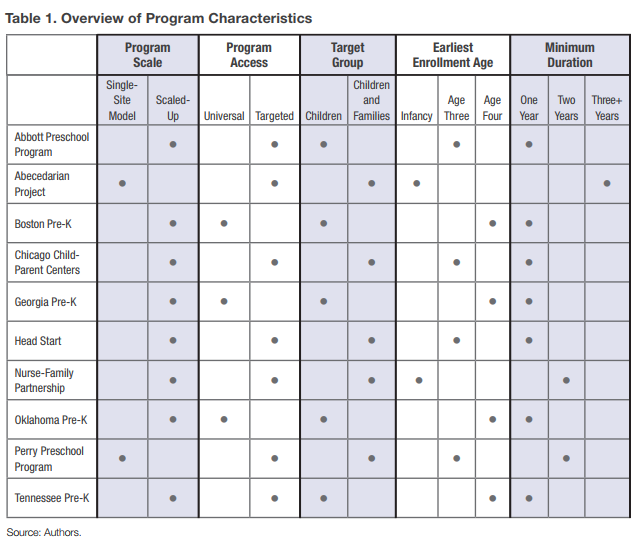

It’s worth noting that the evidence on childhood programs is often conflated. AEI’s Katharine Stevens and Elizabeth English break it down in their excellent, deep-dive report Does Pre-K Work? They illustrate the dangers of drawing sweeping conclusions about research findings, especially when mixing studies about infants with studies of three- or four-year olds. And home visit advocates emphasize that disadvantage begins in utero and infancy, making a standard pre-K program inherently inadequate. This issue is complex, and Congress’ defunding decision will only hurt efforts to gather evidence about how best to level the playing field for children.

2. Why do people reject algorithms?

Researchers want to understand our ‘irrational’ responses to algorithmic findings. Why do we resist change, despite evidence that a machine can reliably beat human judgment? Berkeley J. Dietvorst (great name, wasn’t he in Hunger Games?) comments in the MIT Sloan Management Review that “What I find so interesting is that it’s not limited to comparing human and algorithmic judgment; it’s my current method versus a new method, irrelevant of whether that new method is human or technology.”

Job-security concerns might help explain this reluctance. And Dietvorst has studied another cause: We lose trust in an algorithm when we see its imperfections. This hesitation extends to cases where an ‘imperfect’ algorithm remains demonstrably capable of outpredicting us. On the bright side, he found that “people were substantially more willing to use algorithms when they could tweak them, even if just a tiny amount”. Dietvorst is inspired by the work of Robyn Dawes, a pioneering behavioral decision scientist who investigated the Man vs. Machine dilemma. Dawes famously developed a simple model for predicting how students will rank against one another, which significantly outperformed admissions officers. Yet both then and now, humans don’t like to let go of the wheel.

3. Massive data still does not equal evidence.

For those who doubted the viability of consumer health wearables and the notion of the quantified self, there’s plenty of validation: Jawbone liquidated, Intel dropped out, and Fitbit struggles. People need a compelling reason to wear one (such as fitness coach, or condition diagnosis and treatment).

Rather than a data stream, we need hard evidence about something actionable: Evidence is “the available body of facts or information indicating whether a belief or proposition is true or valid (Google: define evidence).” To be sure, some consumers enjoy wearing a device that tracks sleep patterns or spots out-of-normal-range values – but that market is proving to be limited.

But Rock Health points to positive developments, too. Some wearables demonstrate specific value: Clinical use cases are emerging, including assistance for the blind.

Posted by Tracy Allison Altman on 28-Jul-2017.

Photo credits: Kitty on Laptop by Ryan Forsythe, CC BY-SA 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons, and Wearables Graveyard by Aaron Parecki on Flickr.